Literature of the English Country House: G. W. M. Reynolds and the homes of the wealthy

School of English PhD candidate Jamie Morgan considers the work of George Reynolds to find out about the tastes and behaviour of the aristocracy in the 19th century.

Although George William MacArthur Reynolds is well-known for his depictions of the slums of London, much of his writing focussed on the mansions, country houses and palaces of the higher ranks of society.

These could be just as interesting to Reynolds’ largely working-class readership. His narratives tantalized them with long descriptions of luxurious interiors, making them voyeurs upon a lifestyle of aristocratic extravagance.

Most importantly for the enjoyment of readers, Reynolds was prepared to be far more speculative than most contemporary authors about what went on behind the walls of these dwellings. They were presented as centres of gossip, intrigue and immorality. Reynolds’ highly graphic work was the 19th century version of today’s mass media, particularly its tabloid element.

Seldom do such places stand for decency and moral rectitude. Kingston Grange in Mary Price, with its worthy owner, Squire Kingston, is unusual. It is also, despite the quirky paternalism that reigns there, rather dull.

In sharp contrast, Buckingham Palace in the Mysteries of London becomes the location where the loose morals of the aristocracy and rumours of Royal mental degeneration are discussed. The intruder, the pot-boy Henry Holford, is fascinated by the magnificent surroundings, becoming the eyes and ears of the working-class as he hides under couches listening to the private conversations of the great and not so good.

Just as intriguing for readers was the ease with which other ne’er-do-wells could secretly enter. Reynolds suggests that the "Royal Crib" is open for all, with Henry making repeated visits before being observed and ejected.

The mansion may have yielded poll position to the dens of the metropolis for violence and murder but for sexual encounters it was the clear winner. Women are invariably beautiful and usually willing; clothes reveal rather than conceal their voluptuous figures: age is of little concern since the slenderness of female youth transforms itself with surprising regularity into the alluring embonpoint of the more mature.

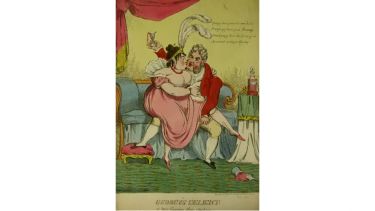

In the Mysteries of the Court of London, Reynolds’ focus upon the libertinism of the Prince Regent offered more opportunities. In Carlton House, he can ponder upon world events while watching ballet dancers display their 'flexibility and grace'.

In many ways Reynolds built upon the popularity of Gothic fiction and brought it into the modern age. The mansions of St James’s and Bloomsbury become places of long-winding passages and secret rooms where the aristocracy inveigle innocent or not so innocent females.

Reynolds’ narratives also followed in the tradition of the scandalous radical cartoons and pamphlets from the early part of the century.

As Mayhew showed, Reynolds’ depictions of life in upper class dwellings encouraged his audience to believe in the immorality of the aristocracy. When a crowd of costermongers listen to the reading of Venetia Trelawney being trapped in the mechanical chair in Leveson House by a fiendish Marquis they cannot contain themselves:

‘”Aye! that’s the way the harristocrats hooks it. There’s nothing o’ that sort among us; the rich has all that barrikin to themselves.” “Yes, that’s the b____ way the taxes goes in,” shouted a woman’ (See: Henry Mayhew, Mayhew’s London, edited by Peter Quennell, Spring Books, p. 67).

In London, poverty-stricken areas, such as the infamous St Giles rookery, might lie close by the dwellings of the wealthy. Their inhabitants might pass these mansions, latest penny number in hand, thinking that they were morally no worse, and probably better, than their so-called social superiors.

Reynolds used his depictions of mansions and palaces as part of his literary armoury to challenge claims that the upper orders were the natural and rightful rulers of society. They promoted the line of the muck-raking popular press, not least his own Reynolds’s Newspaper, which railed against the pampered drones of society who lived upon the public purse. However realistic these portrayals were, they made for extremely popular and frequently exciting reading.

Written by Jamie Morgan, on 16 July 2015.

Find out more about Literature of the English Country House.